APRIL 6, 2019 [updated with funeral details] — Ernest Frederick “Fritz” Hollings, a transformative South Carolina governor who had a 38-year career as a pragmatic, action-oriented United States senator, died today of natural causes in his home on Isle of Palms, S.C., his family announced today. He was 97.

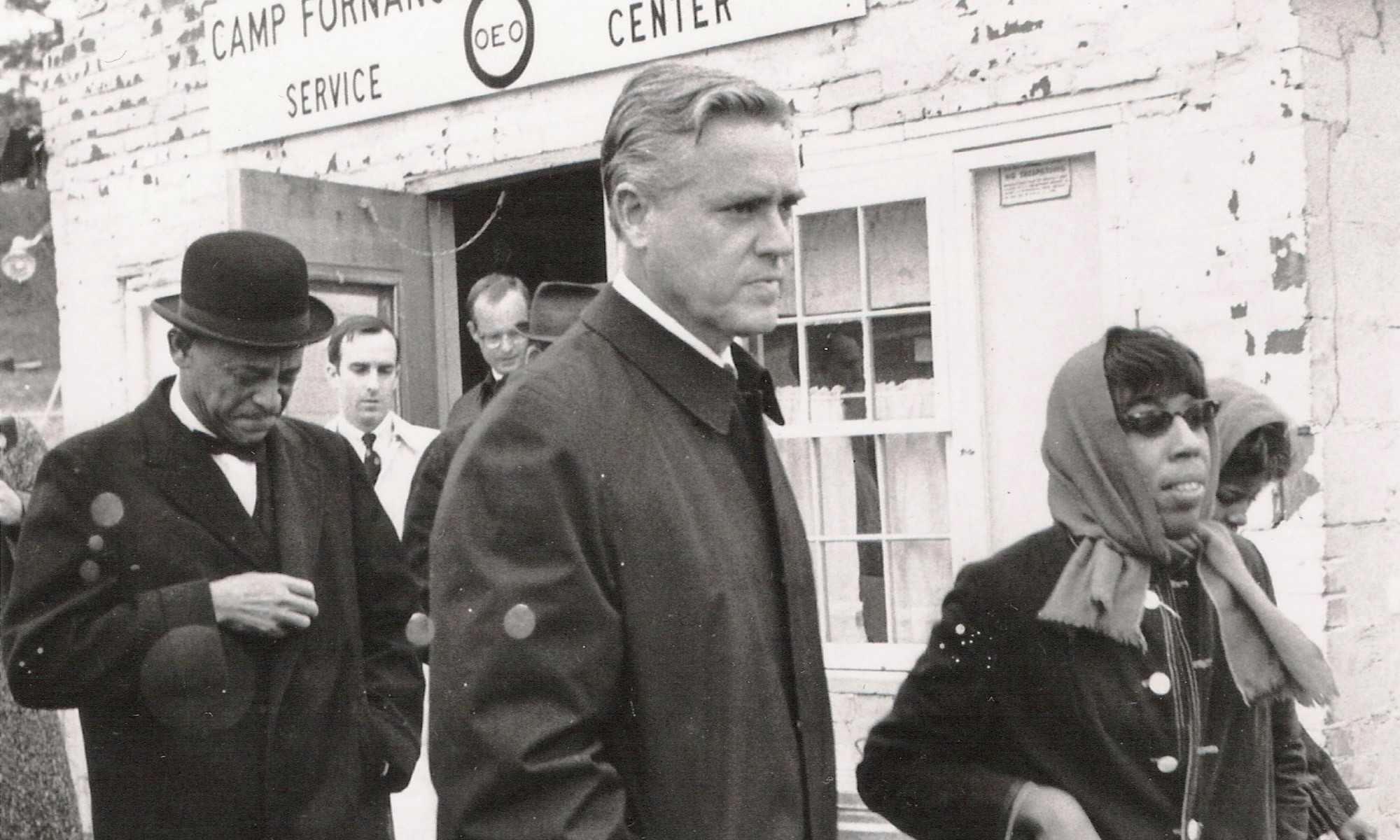

Tall with a shock of white hair, Hollings often mesmerized colleagues with wit, intelligence and a deep Charleston brogue. On the Senate floor and on the campaign trail, Hollings concentrated on a raft of national issues close to his heart, including early Senate victories to protect the environment, alleviate hunger and push for affordable health care early. As his public service continued, he concentrated on balancing the federal budget, arguing for fair trade policies, promoting economic opportunities and unlocking the telecommunications revolution that swept through the country in the last 20 years.

Tall with a shock of white hair, Hollings often mesmerized colleagues with wit, intelligence and a deep Charleston brogue. On the Senate floor and on the campaign trail, Hollings concentrated on a raft of national issues close to his heart, including early Senate victories to protect the environment, alleviate hunger and push for affordable health care early. As his public service continued, he concentrated on balancing the federal budget, arguing for fair trade policies, promoting economic opportunities and unlocking the telecommunications revolution that swept through the country in the last 20 years.

“Our father, Fritz Hollings, was dedicated to his family, the United States Senate and the people of South Carolina,” said his three surviving children, Michael M. Hollings of Columbia, S.C., Helen Hollings Reardon of Glenwood Springs, Colo., and Ernest F. Hollings III of Kissimmee, Fla. “He was a hero for us and millions of Americans. He was so honored to have served the people of this great state in the South Carolina House of Representatives, as lieutenant governor and governor, and as a member of the United States Senate.

“While we are heartbroken, we hope that in the coming days and weeks as we celebrate our father’s life, all South Carolinian’s will be reminded of his service to our state and nation.

In July 2010, former Vice President Joe Biden, who Hollings mentored in the Senate, shared the senator’s importance to South Carolina and the nation during remarks at the dedication of the Ernest F. Hollings Special Collections Library at the University of South Carolina:

“He is always reaching beyond — beyond what he once did, always excelling beyond what anybody thought was possible. He set up a statewide network of technical colleges. That’s an easy thing to say now. But back when he did that, that was way ahead of the curve, way ahead of the curve. … We’re investing over $25 billion now in community colleges and technical colleges. Everybody now in the year 2010 talks about it. You were using the same language we’re doing now, Fritz, back when you were governor.”

Hollings, a lifelong conservative Democrat, was elected governor in 1958 for a four-year term. As governor, he established a well-deserved reputation for economic common sense and laid the foundation for economic growth that has made South Carolina a modern success story. During his gubernatorial service, he balanced the state’s budget for the first time and led it to getting the first AAA credit rating in the South. He recruited international businesses after building a legacy of technical education that emphasized job training.

In 1966, Hollings won the first of seven elections to the United States Senate. He retired in 2005.

During the 2010 library dedication, Biden reminded people of how Hollings’ book, “The Case Against Hunger: A Demand for a National Policy” sparked a national debate on hunger in America. It called for a new government commitment to improving programs for the poor. Hollings believed it is “better to feed the child than to jail the man,” which led to co-authoring of national legislation that created the Special Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants and Children, popularly known as WIC, which was modeled after a pilot program in South Carolina’s Beaufort County.

“Fritz was the first person on a national political scale talking about how a child cannot learn, a child cannot develop, a child cannot have an even shot at their place in this society, if they don’t have the nutrition when they’re young,” Biden said. “It wasn’t just about hunger. It wasn’t just about poverty, which was critically important. It wasn’t an extension of the New Deal. It was a new idea, a new idea.”

Born on New Year’s Day in Charleston, S.C., in 1922, Hollings was a son of Wilhelmine Dorothea Meyer and Adolph Gevert Hollings Sr. Raised with three siblings in the Hampton Park Terrace neighborhood during the Depression, he was a precocious student, entering The Citadel at age 16 in 1938. He graduated in 1942 and immediately received a commission from the U.S. Army. He served as an officer in the North African and European campaigns in World War II, receiving the Bronze Star and seven campaign ribbons. When he returned from the war, he entered the University of South Carolina School of Law. Working through holidays and summers, he graduated in 1947 — less than three years after he began.

The following year at age 26, he began his long career of public service when he was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives. In his second term, his peers voted him Speaker Pro Tempore, a post to which he was re-elected in 1953. Two years later, he became Lieutenant Governor. In 1958, recognizing his leadership, achievements and dedication to public service, the people of South Carolina chose him for the highest office in the state. At 36, he was the youngest man in the 20th century to be elected Governor of South Carolina. While governor, Hollings forcefully reminded citizens and leaders that South Carolina was governed was by the “rule of law,” which led to the peaceful integration of Clemson University.

In 1962, Hollings sought the Democratic nomination to U.S. Senate, but lost in a primary to incumbent U.S. Sen. Olin D. Johnson. After he died in 1966, Hollings ran again to start his tenure in the Senate, where he became the longest-serving junior senator to Republican colleague Strom Thurmond.

Hollings, who some said looked like a senator out of Hollywood central casting, was also quick to establish what a longstanding commitment to environmental policies when, in 1972, he wrote and steered through Congress the National Coastal Zone Management Act, the nation’s first land use law designed to protect coastal wetlands. In the early- and mid-1970s, he also pushed to establish the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), authored the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and fought for passage of the Ocean Dumping Act and the Fishery Conservation and Management Act.

Hollings also served as a chair and ranking member on the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee where he championed a wide range of issues such as telecommunications, transportation security, consumer protection, coastal preservation and research and trade policy. As a principal author of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, Hollings worked to promote competition within the telecommunications industry and to ensure that consumers benefited from innovative technologies at reasonable prices. As a result of the September 11 attacks, Hollings led the effort to pass transportation security legislation for our nation’s port, railroad and aviation systems in an effort to bolster national security and protect American citizens.

Hollings also was instrumental in guiding U.S. trade policy in the Congress. He sought to reinvigorate economic competitiveness and protect American jobs, while improving U.S. manufacturing and production capabilities, including South Carolina’s textile industry. Additionally, Hollings believed that greater understanding and improved management of ocean and coastal ecosystems were essential to maintain healthy coasts and to prepare communities for natural hazards such as hurricanes..

Hollings also sat on the Senate Budget Committee, which he chaired in the 1980s to try to take the country down the path to “true surplus.” He was the first voice in the Senate to decry the practice of looting Social Security, Medicare and other trust funds to camouflage the size of the deficit. He pushed for a freeze of federal spending and fought for fiscal responsibility, constantly pressing Congress to put the nation back on a “pay-as-you-go” basis rather than burdening future generations with escalating federal deficits and debt.

As a senior Democrat on the Senate Appropriations Committee and its Commerce, Justice and State Appropriations Subcommittee, Hollings used his seniority, experience and know-how to fight for responsible government and South Carolina’s fair share. He initiated a nationwide effort to combat breast and cervical cancer by using his seat on the Appropriations Committee to secure funding for a pilot screening program. Thanks to Hollings, South Carolina was among six states selected for this landmark initiative, which screened tens of thousands of South Carolina women and detected hundreds of occurrences of cancer. The Medical University of South Carolina today is the home of the Hollings Cancer Center. On a national level, Hollings was primary leader to start federally-funded community health centers that today provide affordable health care at thousands of clinics to more than 27 million people.

Throughout his Senate career, Hollings steered millions of federal dollars to pay for health programs, fund infrastructure projects, improve public education, attract new businesses and protect the environment in South Carolina.

Hollings was predeceased by his second wife, the former Rita Louise “Peatsy” Liddy, who died in 2012 after an eight-year battle with Alzheimer’s. With his first wife, the late Patricia Salley Hollings, he had four children: Michael Milhous Hollings (Deborah-Anne) of Columbia; Helen Hollings Reardon (John) of Glenwood, Colo; Salley Hollings Schwerdt (deceased); and Ernest Frederick Hollings III of Kissimmee, Fla.; and a surviving sister, Barbara Hollings Siegling of Charleston, and a brother-in-law, Claude Baldwin of Charleston. He had seven grandchildren: Salley Hollings Nunn (Knox) of New Orleans, La.; Patricia Salley Schwerdt of Florida; Steffani Conner Schwerdt of Charleston; Christopher Charles Milhous Hollings of Columbia; John Elliott Reardon II (Ilse Niemeyer) of Denver, Colo.; Dain Frederick Reardon (Jessica Merritt) of Denver, Colo.; and Patrick Hayne Reardon of Los Angeles, Calif.; and 10 great-grandchildren, and several nephews, nieces and other relatives.

Hollings was a lifelong member of St. John’s Lutheran Church in Charleston. A member of the South Carolina and American Bar associations, he was a member of several Charleston organizations, including the Hibernian Society (past president), the St. Andrew’s Society, BPO Elks and the Association of Citadel Men. He won numerous awards. In 2017, a statue honoring him was unveiled outside of the federal courthouse in Charleston.

Funeral arrangements are being handled by James A. McAlister Funerals and Cremation.

- Visitation: 3 p.m. to 6 p.m., Sunday, April 14, 2019, at James A. McAlister Funerals and Cremation, 1620 Savannah Highway, Charleston, SC 29407

- Public observance: Sen. Hollings’ body will lie in state 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday, April 15, 2019, in the South Carolina Statehouse, 1100 Gervais St., Columbia, S.C.

- Funeral: 11 a.m. Tuesday, April 16, 2019, at Summerall Chapel, The Citadel, 171 Moultrie St., Charleston, S.C.

In lieu of flowers, memorials can be made to the Hollings Cancer Center. Please designate on the memo line in memory of Senator Hollings and make checks payable to: MUSC Foundation – Hollings Cancer Center, Office of Development, 86 Jonathan Lucas Street, MSC 955, Charleston, S.C., 29425.

Media inquiries: Contact Andy Brack, 843.670.3996. We request that you direct inquiries here and not to the family.

Thank you, senator: “No one in modern time has given as much to South Carolina as Fritz Hollings. In seven decades of public service – starting as a young officer in World War II to becoming governor to being elected seven times to the United States Senate, Hollings has given back in big ways.” Read more here:

http://www.statehousereport.com/2019/04/06/fritz-hollings/

As usual Andy, you have eloquently represented all of us who were lucky enough to have worked for and with

Sen. Hollings. He was a visionary, a patriot, a pragmatic polition, a friend,

A leader and the most intelligent and capable person i have ever known. He

Is and will be missed. All of us and all South Carolinians were blessed to have

him for 97 years